Worcester, Massachusetts, the site of the first two National Woman’s Rights Conventions in 1850 and 1851, was also home to the Oread Collegiate Institute, one of the places women’s suffrage pioneers met to plan those historic gatherings.1 Founded by Eli Thayer with the assistance of Lydia Maria Child, two presidents of Brown University, and a number of other influential supporters, it was among the oldest women’s colleges in the United States. Its mission was to ensure that “women have the same opportunity of study and intellectual development” as men.2

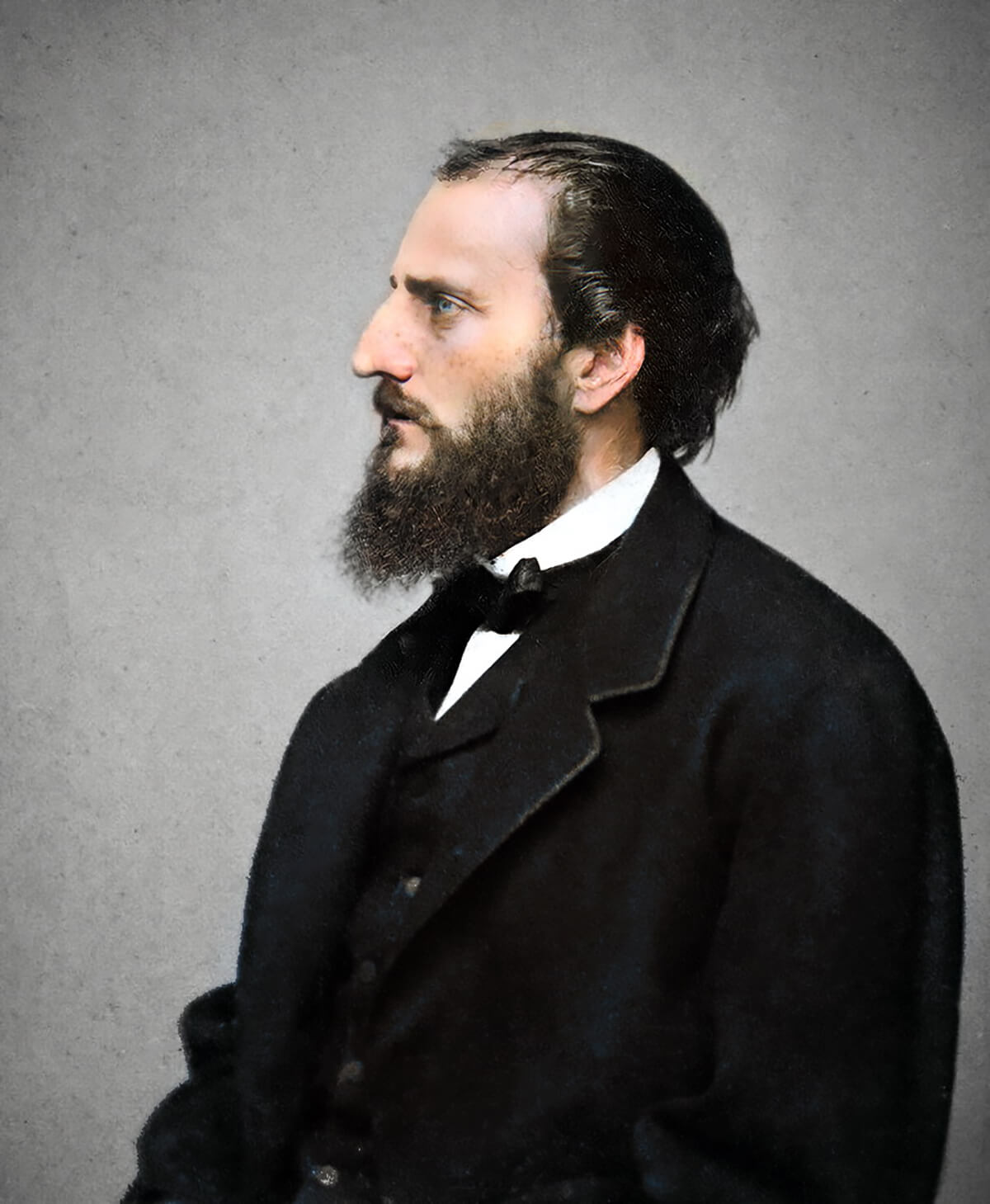

In 1854, Thayer was a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives representing Worcester. He had watched with dismay as the Kansas-Nebraska bill, with its threat to open up these U.S. territories to slavery, proceeded inexorably toward passage in Washington. He realized that once the bill was law, people in the North would want “nothing so much as to make Kansas a free State, but they were in the dark about the modus operandi.” He set his mind to the problem, and developed a plan. Thayer called it “organized emigration,” by which he meant encouraging “supporters of free labor and opponents of slave labor” to settle in Kansas and vote in the plebiscites that would determine its future.

Under Thayer’s plan, the emigrants would receive free or heavily subsidized railroad and stagecoach transportation, provisions, and lodging en route. More than that, his proposed Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Society would pay for capital improvements in their new home, such as saw mills, grist mills, power plants, manufacturing equipment, and printing presses. All of this would be funded by private capital. Everywhere in the territories where this up-front investment was made, Thayer believed, there would inevitably follow “a whole township behind it, including a school, a church, and a newspaper.”3 In this way Kansas could quickly be populated with, he estimated, “20,000 persons from Massachusetts.”4

Under Thayer’s plan, emigrants would receive free or heavily subsidized railroad and stagecoach transportation, provisions, and lodging en route. In this way Kansas could quickly be populated with, he estimated, “20,000 persons from Massachusetts.”

Thayer brought his proposal to the Massachusetts legislature in April, more than a month before the Kansas-Nebraska Act was signed into law. On May 4, 1854, the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company received its charter of incorporation from the Commonwealth.5 It provided for an initial capitalization of up to $170 million in today’s currency, the first seven million of which was to be to be raised from private donors and expended in 1854. Gerrit Smith, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s cousin and one of the nation’s wealthiest men, would eventually contribute.6

“The rumor of such an expense served the great purpose of freedom better than the expenditure could have done,” one of the original directors recounted, which was fortunate because nowhere near the proposed capitalization was ever raised, let alone spent. In the summer of 1854, only six small groups of settlers headed for Kansas, numbering about 450 people.7

It was, nonetheless, a noteworthy beginning. Susan B. Anthony’s brother Daniel Read Anthony would be in the very first group of twenty-nine settlers.8

By the time they left the Eastern Seaboard, the proslavery forces were already well ahead of them. Five hours before sunrise on May 26, 1854, the Senate passed the final House version of the Kansas-Nebraska bill. Oblivious to the disaster they had wrought, partisans celebrated with a 100-gun salute from Capitol Hill, while the weary Senators attempted to slip through the inebriated crowds and make a beeline for their beds. When President Franklin Pierce signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act four days later,9 hundreds of people crossed the border from the slave state of Missouri into Kansas and staked out their areas of land. Several of the new Kansas landowners then convened to adopt rump local ordinances, among which were these resolutions:

That we will afford protection to no abolitionist as a settler of this Territory.

That we recognize the institution of Slavery as already existing in this Territory, and advise slaveholders to introduce their property [sic] as early as possible.10

It was a few weeks later in June when, prompted by publicity in the New York Daily Tribune, an antislavery meeting in Rochester convened to generate support for Thayer’s emigrant aid mission to Kansas.11 It is likely that Susan Anthony’s brother Daniel attended,12 because he received a personal invitation from Eli Thayer to join the very first mission in July. As Daniel later recounted:

Eli Thayer, of Massachusetts, wrote to me at Rochester, N.Y., requesting me to join the emigrant aid party then about starting from the East to settle in the territory of Kansas. I promptly accepted the invitation and joined the party at Rochester on its way to the land of the border ruffians.13

The first party of the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company headed out from Boston on July 17, with Eli Thayer in the vanguard. Rochester was the first stop along their route, where Daniel Read Anthony joined them. On their way the adventurers sang “The Emigrant Aid Song,” with lyrics provided to the group as a bon voyage gift from John Greenleaf Whittier. They set the poet’s composition to the tune of “Auld Lang Syne”:

We cross the prairie as of old

The Pilgrims crossed the sea

To make the West, and they the East,

The homestead of the free!

We go to rear a wall of men

On freedom’s Southern line

And plant beside the cotton tree

The rugged Northern pine.14

With Anthony now on board, Thayer bid his pioneers farewell at Buffalo. It would be a further two weeks before the little convoy arrived in Kansas. Much faster than they could reach their destination, news traveled to Missouri’s slaveholders that New England emigrants were headed their way. The slaveholders in western Missouri did not take well to the prospect of East Coast abolitionists as neighbors, and they became even more alarmed when they heard the exaggerated report that Thayer’s organization envisioned spending millions of dollars to send tens of thousands of antislavery settlers into Kansas. The slave men had their own multimillions to protect. According to estimates at the time, their investment in human “property” in Missouri alone was more than $1.5 billion, measured in today’s currency.15

Though the party of settlers inching towards Kansas was in fact tiny, the news that hordes of abolitionists were coming immediately prompted Missouri’s slaveholders to take more aggressive action. Jackson County, which encompassed St. Louis, adopted a resolution pledging to “remove any and all emigrants” crossing into Kansas “who go there under the auspices of the Northern Emigrant Aid Societies.” The Squatter Sovereign, a proslavery organ established that summer in the newly founded town of Atchison on the Kansas side of the Missouri River, put the threats more bluntly. Missourians will, the paper announced, “lynch and hang, tar and feather and drown, every white-livered abolitionist who dares to pollute our soil.”16

According to estimates at the time, the slaveholders’ investment in human “property” in Missouri alone was more than $1.5 billion, measured in today’s currency.

This is what awaited Daniel Anthony at his destination. He anticipated as much. “I came,” he said, “because, under the teachings of Garrison, Sumner, Gerrit Smith, and Thad. Stevens, I had been brought up to detest the methods by which the political slave power of the country was seeking to rob this free government of its birth-right of free territory.”17

Once they arrived in Kansas, Anthony’s party set to work scouting out locations suitable for settlement. In short order the group selected a site in the Kaw River valley to become the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Society’s first town, which they named after the Society’s treasurer and benefactor, Boston textile manufacturer Amos Lawrence. Anthony chose a quarter section of land there for himself, near a spring on a rocky hill that overlooked the future town from an elevation of a thousand feet. It would later be christened Mount Oread, in honor of Thayer’s women’s college.18 In a matter of months, the township of Lawrence was formally established.19

Within two years, Lawrence, Kansas would become infamous across the American continent. The cannon fire and the battle cries of marauders that soon resounded there would be heard a thousand miles away, and reverberate a thousand times more loudly, in the already embattled halls of Congress.

— Christopher Cox

Footnotes

- “The Places Where Worcester’s Reformers Met,” Worcester Women’s History Project, www.wwhp.org/about-us. ↩︎

- Martha Burt Wright, ed., History of the Oread Collegiate Institute, Worcester, Mass. (1849-1881), with Biographical Sketches (New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor Co., 1905), 1, 5. ↩︎

- Eli Thayer, Six Speeches, with a Sketch of the Life of Hon. Eli Thayer (Boston: Brown and Taggard, 1860), 5-7. ↩︎

- New England Emigrant Aid Company, Nebraska and Kansas: Report of the Committee of the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Co., with the Act of Incorporation and Other Documents (Boston: Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Co., 1854), 6. ↩︎

- New England Emigrant Aid Company, Nebraska and Kansas, 3-4. This initial corporate charter was superseded by two others, with the final version changing the name to “The New England Emigrant Aid Company” issued by Massachusetts in February 1855. It is this name by which the company became well known in Congress. Samuel A. Johnson, “The Genesis of the New England Emigrant Aid Company,” The New England Quarterly, vol. 3, no. 1 (January 1930), 95-122. ↩︎

- M. Leon Perkal, “American Abolition Society: A Viable Alternative to the Republican Party?,” Journal of Negro History, vol. 65, no. 1 (January 1, 1980), 57, at 60. At one point Smith pledged over $100,000 in today’s currency to the effort. “Biographical History,” Gerrit Smith Papers, Syracuse University Libraries Special Collections Research Center. But ultimately he did not become a stockholder of the New England Emigrant Aid Company. Samuel A. Johnson, “The Genesis of the New England Emigrant Aid Company,” The New England Quarterly, vol. 3, no. 1 (January 1930), Appendix II, 121. After his death, an essay on his philanthropy stated that he contributed $16,000 to “keep slavery out of Kansas,” which would amount to over one-half million dollars in today’s currency. “Gerrit Smith,” Rutland (VT) Daily Herald, February 4, 1878, 4. ↩︎

- Edward Everett Hale, “A Quarter Century of Kansas,” The Independent, vol. 31 (September 25, 1879), 1608. While Hale puts the group at 30, this is a rounded approximation; it was 29 when Anthony joined in Rochester and became 31 when two company agents joined in St. Louis. James L. Crabtree, “Daniel Read Anthony, 1824-1904: A Forgotten Chapter in Kansas History” (master’s thesis, Kansas State Teacher’s College of Emporia, 1964), 20-21. ↩︎

- Richard Cordley, A History of Lawrence, Kansas from the First Settlement to the Close of the Rebellion (Lawrence, KS: E.F. Caldwell, 1895), 4. ↩︎

- D. W. Wilder, Annals of Kansas, 1541-1885 (Topeka: T. Dwight Thatcher, Kansas Publishing House, 1886), 44. ↩︎

- Horace Greeley, The American Conflict: A History of the Great Rebellion in the United States of America, 1860-64 (Hartford: O. D. Case & Co., 1864), 1:235. ↩︎

- Dr. John Doy, A Plain, Unvarnished Tale: Narrative of John Doy, of Lawrence, Kansas (New York: Thomas Holman, Book and Job Printer, 1860), 132, quoted in D. W. Wilder, Annals of Kansas, 294. ↩︎

- James L. Crabtree, “Daniel Read Anthony, 1824-1904: A Forgotten Chapter in Kansas History” (master’s thesis, Kansas State Teacher’s College of Emporia, 1964), 18-19. ↩︎

- Charles S. Gleed, ed., The Kansas Memorial: A Report of the Old Settlers’ Meeting Held at Bismarck Grove, Kansas, September 15-16, 1879 (Kansas City, MO: Ramsey, Millett & Hudson, 1880), 108. ↩︎

- Cordley, A History of Lawrence, 47; Horace Andrews, Jr., “Kansas Crusade: Eli Thayer and the New England Emigrant Aid Company,” The New England Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 4 (December, 1962), 497-514, at 501-02 and n. 2. ↩︎

- Harrison Anthony Trexler, “Missouri Slavery as an Economic System,” Slavery in Missouri 1804-1865 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1914), 10, citing census figures of 87,422 enslaved people in Missouri as of 1850, and 114,931 as of 1860; ibid. at 39-42: “The golden age of slave values is the fifties [1850s]” … although the “fabled $2,000 negro is found more often in story than in record … stout hemp-breaking negroes ‘sold readily from $1,200 to $1,400.’” Women frequently were sold for over $1,000, and the price for children was often in excess of $500. Ibid., 39-42. Using $500 as the most conservative estimate for all enslaved persons, and multiplying that by the mean enslaved population of 101,000 at mid-decade, the total is $50.5 million, or $1.8 billion in current dollars. Given the values Trexler cites, the actual figure could be two or three times greater. ↩︎

- Greeley, The American Conflict, 1:235-36; W. W. Admire, “An Early Kansas Pioneer,” Magazine of Western History, vol. 10, no. 5 (September 1889), 688. ↩︎

- Admire, “An Early Kansas Pioneer,” 688. ↩︎

- Daniel R. Anthony, autobiographical sketch (1907), Kansas Biographical Scrapbooks, series A, vol. 3, Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, 178. ↩︎

- Cordley, A History of Lawrence, 9-10. ↩︎