In the midsummer of 1914, baseball, tennis, and sailing dominated the news, the sun was shining, and the federal government’s finances were sunny, too. The federal budget was in balance, and interest payments on the modest debt were an insignificant expense item1. In dollar figures, the public debt stood at $2.9 billion—less than $29 per person in America at the time2. Adjusted for inflation, today that would be $894 per capita. Compare that with our actual situation, when the debt per capita has reached $103,000—115 times as much.3

On July 30 of that summer, President Woodrow Wilson gave a brief news conference. A reporter asked, “Mr. President, have you taken any action at all on behalf of this government in connection with the war in Europe?”

Wilson answered in two words: “No, sir.”

Another reporter followed up: “Mr. President, have you gone at all into the probable effect of the European war on business conditions in this country?”

The president responded, “Not at all yet.”4

That same day, J.P. Morgan held an emergency meeting at his New York City offices. The men who crowded around his conference table were the officers of the nation’s largest banks: Chase National Bank, First National Bank, Bankers Trust, Guaranty Trust—as well as the President of the New York Stock Exchange. Archduke Franz Ferdinand had been assassinated a month earlier. Two days ago, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. The world stood on edge as Russia mobilized for war against Austria-Hungary.

When Congress declared war against Germany on April 14, 1917, the federal spending spigots opened wide.

The panic over the threat of a broader war led securities exchanges throughout Europe to close their doors to trading. In England the market remained technically open, but there were no buyers. Every investor and government in Europe desperately sought to liquidate its holdings, and America remained the only major market open.

The bankers left Morgan’s conclave and announced to the press that they saw no reason to close the New York Stock Exchange. America, they were certain, would be largely immune from the European conflict. In fact, by remaining neutral, America could supply food, textiles, and manufactured goods to the suffering populations. And since this business would be done on credit, not only America’s producers but America’s bankers would profit.5

The next morning, those confident bankers awoke to headlines announcing that both France and Britain could soon be drawn into the war.6 This conflict was to be a pan-European disaster. Morgan summoned them back to another meeting that very day. This time, they decided that the NYSE would shut down immediately and indefinitely.7 To everyone in America at the time, it was shocking and unthinkable that this could happen.

The new reality demonstrated two things. First, America, while remaining neutral, would hardly be unaffected. And second, the government and businesses would struggle to raise new capital without an efficient market to facilitate it.

By late 1914, it became clear the stock market would have to reopen. It did on November 28, but only for restricted business. It did not fully reopen for normal operations until April 1915—after a stoppage of nearly nine months, by far the longest closure in history, before or since.8

For the next two years, the United States stayed out of the war. Wilson ran for reelection in 1916 as the peace candidate, and by all accounts he narrowly won reelection for that reason. Although there was much talk of preparedness, military spending remained tiny, and the federal budget remained in balance.

But this budget equipoise was short lived. Germany took America’s resolute neutrality for weakness and unleashed its policy of unlimited submarine warfare on merchant shipping in international waters. Suddenly everything changed.

When Congress declared war against Germany on April 14, 1917, the federal spending spigots opened wide. In the peacetime years of Wilson’s presidency, federal spending amounted to about $725 million per year, or $17 billion in today’s currency. In 1916, the last year before America entered the war, the federal government had run a surplus equal to 7% of that total budget. Surpluses back then were common. It was the deficit years that were the exception. Up to that point, Wilson had run a surplus or broken even in three of his four budget years.

But beginning in April 1917, the massive new wartime spending generated progressively higher deficits, totaling $23.248 billion by the time the peace treaty was signed in Versailles. That’s equal to nearly a half trillion dollars ($426 billion) in today’s currency. Keep in mind the peacetime federal budget was $725 million. In just two and a half years, the nation added to its debt by an amount equal to thirty-two years of peacetime federal spending.

It would be “most unwise,” Wilson said, to finance the war “entirely on money borrowed.” The Treasury Secretary warned against financing the government “upon the quicksands of inflation or unhealthy credit expansion.”

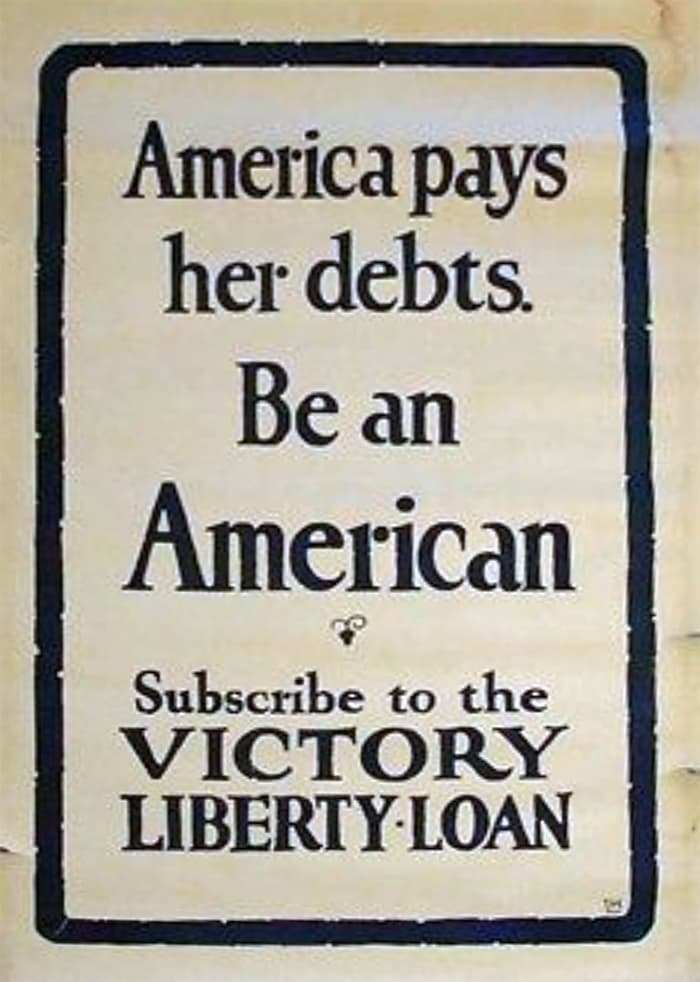

Fortunately for the nation, the “Hamiltonian norm”—the notion that the U.S. government would always work to repay its debts—remained alive and well. It may seem shocking to us now, but back then Democrats and Republicans alike saw the importance of keeping federal borrowing to a minimum, and of repaying debt as quickly as possible.

Woodrow Wilson and Treasury Secretary William McAdoo said almost exactly that in their public pronouncements. In his war message to Congress on April 2, 1917, Wilson spoke of the borrowing that would be needed to finance the war and reminded both the House and the Senate of their duty “to protect our people … against the very serious hardships and evils which would be likely to arise out of the inflation which would be produced by vast loans.” It would therefore be “most unwise,” Wilson said, to finance the war “entirely on money borrowed.”9

The president proposed a partial pay-as-you-go approach, which McAdoo fleshed out as one-third taxation and two-thirds borrowing. The Treasury secretary warned against financing the government “upon the quicksands of inflation or unhealthy credit expansion,” which he feared would “bring ultimate destruction upon the country.”10

McAdoo’s postwar successor as Treasury Secretary, Andrew Mellon, agreed. To let the debt linger, or worse to grow, he said, was a sign of national “debility.”11

The federal income tax had been in place only five years at this point, and there was a meager experiential base on which to judge appropriate levels for tax rates. In the crisis of the Great War, members of Congress in both parties were willing to support the Wilson administration’s request for income tax rates that topped out at 77%.12

But the sky-high rates soon proved suboptimal. High-bracket taxpayers whose income came from investments could—and quickly did—rearrange their affairs to shield them from taxation. In 1916, when the top rate stood at 15%, approximately 1,300 taxpayers reported income in the highest bracket. Two years later, when the top rate reached 77%, only 627 tax returns showed income in the highest bracket.13

The Treasury learned the same lesson with its sale of war bonds. The first Liberty Bonds in April 1917 gave investors tax-free income on up to $30,000 in bonds (that’s more than $700,000 today). When the Treasury changed its policy for the next three tranches of Liberty Loans, significantly limiting the tax exemption, wealthy investors bought state and municipal debt instead. By doing so, they avoided the 77% federal income tax.14 It became harder for the Treasury to sell its Liberty Bonds.

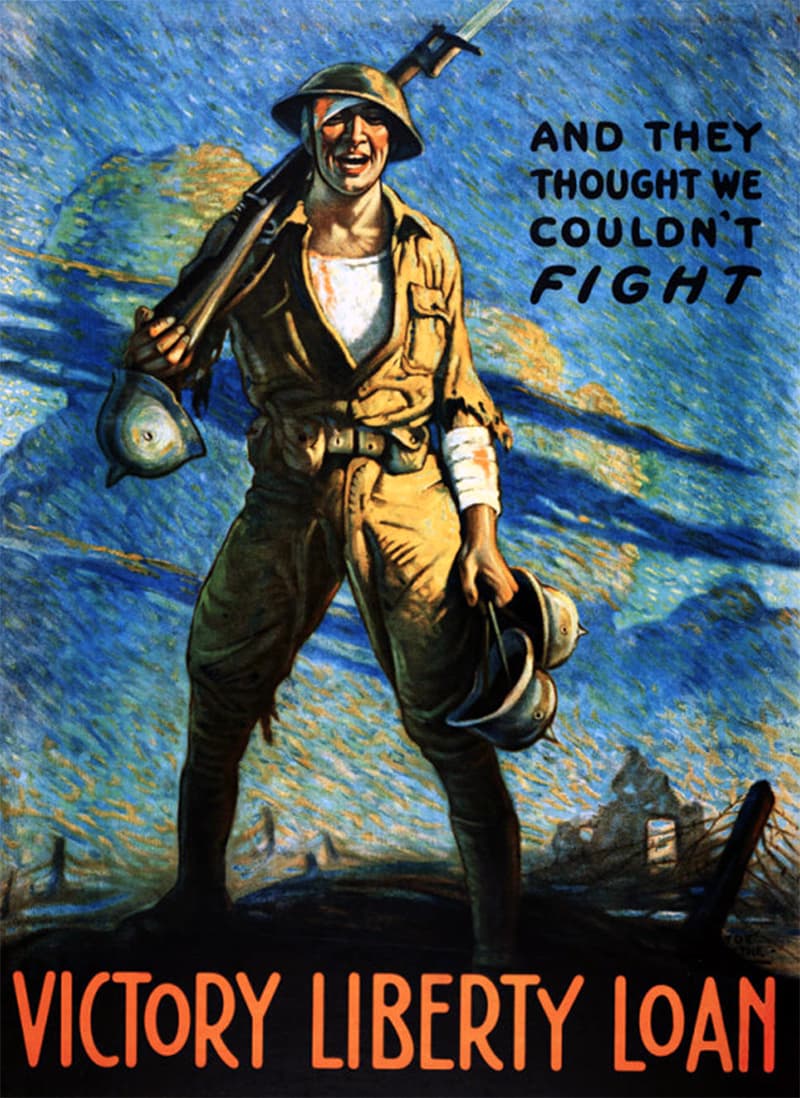

By the time of the fifth and final installment of war bonds, the so-called Victory Liberty Loan, the federal government made the bonds completely exempt from all income taxes. The Treasury placed no limit on the amount that could be purchased with this benefit.

After the war, it fell to President Warren Harding and, after his untimely death, President Calvin Coolidge to deal with paying down the $26 billion in Liberty Loans and other government borrowings that had swelled the national debt.15 They took to heart the hard lessons learned from experimentation with near-confiscatory tax rates. While they set to work reducing federal spending to normal levels, they brought tax rates down to earth as well. Tax rates fell every year from 1921 to 1925—the top rate finally settling at 25%.16

Congress supported these policies. “We have a huge legacy of debts,” explained Senate Majority Leader Henry Cabot Lodge in 1921, “which must be dealt with…. Expenditures must be cut down. Every effort must be made to reduce … the taxation made necessary by the war.”17

By 1924, Harding, Coolidge, and Congress had cut federal spending by 84% compared to the peak wartime level of 1919. In that year alone they paid down nearly $1 billion in debt—equivalent to $17 billion today.18 Between 1920 and 1928, the government paid off 36% of the entire national debt.19

That is, however, the end of this happy part of the story. The rest of the First World War debt remains unpaid. We have been paying interest on it for over 100 years. It’s part of our now $34 trillion debt, over 40% of which was added in the last seven years.20 In 2024, interest on the debt will be more than all defense spending; and by itself, it will consume one-third of all the income taxes paid by individual Americans.21

— Christopher Cox

Footnotes

- Benjamin U. Ratchford, “History of the Federal Debt in the United States,” American Economic Review, vol. 37, no. 2 (May 1947), 131-41, at 135. ↩︎

- U.S. Treasury, “Historical Debt Outstanding,” as of July 1, 1914. ↩︎

- Peter G. Peterson Foundation, “National Debt Per Person,” March 2, 2024. ↩︎

- Presidential News Conference, July 30, 1914, in Arthur S. Link, ed., The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, vol. 50 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985), 528. ↩︎

- “Bankers Here Confer on War,” New York Times, July 31, 1914, 1. ↩︎

- “London Fears the Great Conflict Is About to Begin,” New York Times, July 31, 1914, 1; “German Army Is Expected to Take Field Today,” Washington Post, July 31, 1914, 1; “England Ready for Hostile Move by Germany,” Los Angeles Times, July 31, 1914, 1; “Paris Sees No Escape from Great European Conflict,” New York Tribune, July 31, 1914, 2. ↩︎

- “Governors Close Stock Exchange,” New York Times, August 1, 1914, 1. ↩︎

- Mary A. O’Sullivan, Dividends of Development: Securities Markets in the History of U.S. Capitalism, 1866-1922 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 331-32; Mira Wilkins, The History of Foreign Investment in the United States, 1914-1945 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004), 9-11, 638 note 12. ↩︎

- Woodrow Wilson, Address to a Joint Session of Congress, April 2, 1917, in Arthur S. Link, ed., The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, vol. 41 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), 519. ↩︎

- William G. McAdoo to Woodrow Wilson, May 23, 1918, in Arthur S. Link, ed., The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, vol. 48 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985), 121. ↩︎

- David Cannadine, Mellon: An American Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 318; Sun Won Kang and Hugh Rockoff, “Capitalizing Patriotism: The Liberty Loans of World War I,” Financial History Review, vol. 22, no.1 (April 2015), 45-78. ↩︎

- That highest tax rate came with the Revenue Act of 1918, enacted in 1919 but retroactive to tax year 1918 and in effect to 1921. Revenue Act of 1918, 40 Stat. 1057; Historical U.S. Federal Individual Income Tax Rates & Brackets, 1862-2021, Tax Foundation.org. ↩︎

- Daniel C. Munson, “Treasury Truisms: America’s First Experience with a Steeply Progressive Income Tax,” Financial History, Issue 141 (Spring 2022), 32-35, at 33. ↩︎

- Cannadine, Mellon, 287. ↩︎

- The total increase in federal government debt represented by the Liberty Loans and other government borrowings through August 1919 was $25.596 billion. “Government Securities,” Los Angeles Times, October 5, 1922, IV, 9. ↩︎

- Historical U.S. Federal Individual Income Tax Rates & Brackets, 1862-2021, Tax Foundation.org. ↩︎

- “Lodge Sees Legacy of Debt,” New York Times, August 11, 1921, 9. ↩︎

- President’s Budget for Fiscal Year 2024, Historical Tables, Table 1.1, Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits: 1789-2025 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2023), 24. ↩︎

- U.S. Treasury, “Historical Debt Outstanding,” 1920-28. ↩︎

- Ibid., 2017-present. ↩︎

- Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024 to 2034, Tables 1.1, 1.6, 1.7 (Washington, D.C.: CBO, 2024). ↩︎