When Elizabeth Cady, daughter of a prosperous lawyer, former slaveowner, and former member of Congress from New York, met her future husband Henry Stanton in the fall of 1839, the nation’s desultory steps towards women’s civil rights were gradually beginning to quicken. But the movement for abolition was already galloping forward.

Elizabeth and Henry were introduced at the home of her cousin, Gerrit Smith, a prominent abolitionist, wealthy philanthropist, and future member of Congress.1

Henry was, as Elizabeth described him, “fine-looking”—a man “in his prime” possessed of “remarkable conversational talent.” But it was his antislavery passion that immediately interested her. Henry’s father had been a slaveowner, just as her own father had been; and based on Henry’s youthful experience with slavery in his own household, he had decided early in life that he would do everything he could to bring slavery to an end. Elizabeth knew him by reputation as “the most eloquent and impassioned orator on the anti-slavery platform.”2

From his work as an executive of the American Anti-Slavery Society, Henry had come to view voting rights as the key to achieving political results. This conviction was reflected in a resolution to that effect that he would offer at the American Anti-Slavery Society convention later that year. “Slavery is a creature of law,” his resolution stated, “and can be entirely abolished … only by political action at the ballot box.”3

Elizabeth, at twenty-four a decade younger than Henry, fell in love with his ideas and the brilliant company of his associates as much as with the man himself. “I never had so much happiness,” she recalled of the days after their first meeting. “I felt a new inspiration in life and was enthused with new ideas of individual rights.” Antislavery, she believed, “was the best school the American people ever had on which to learn republican principles and ethics.” Discussing these things with Henry and the other luminaries at her cousin’s fireside was, she recalled a half century later, “among the great blessings of my life.”4

Elizabeth Cady and Henry Stanton were married the following year, against her father’s wishes but not without his blessing. (By this time her father had become sympathetic to the antislavery cause, but he questioned the judgment of people like Henry who agitated for immediate abolition).5 She wore the traditional white dress but struck the traditional “obey” from their marriage vows.6 For their honeymoon twelve days later, the couple traveled to the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London.7 Beyond celebrating their wedding, the trip might have symbolized a marriage of the abolition and suffrage causes—except that Elizabeth and Henry, as well as most of their colleagues in the abolitionist movement, had not yet come to the view that women should vote.

In fact, the question of whether women should even be admitted as members of Henry Stanton’s own American Anti-Slavery Society had created a schism in the organization beginning the year before.8 Now, at the World Anti-Slavery Convention across the Atlantic, women would be made to endure a similar indignity. The organizers of the convention were flatly opposed to women participating as delegates. Despite knowing this before they left, seven American women made the trip across the Atlantic, Elizabeth among them, in the hope that reason would prevail once they arrived.9

In the event, a compromise was struck: Women could attend, but they would have to sit in a segregated area separated by a low curtain, participating only as silent spectators.

Elizabeth did not take this well. Neither did another American at the convention, the prominent abolitionist Lucretia Mott, a former Quaker preacher turned social reformer who was twenty-two years Elizabeth’s senior. In 1833 she had co-founded the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, which included Black women within its leadership and membership. Though Mott and Henry had long been colleagues, the two women had never before met. They quickly bonded over the shared affront of being forced to sit in silence through what Elizabeth described as “twelve of the longest days in June.”10

The matter would not rest there. Elizabeth in particular was stung by the hypocrisy of men eloquently defending the natural rights of enslaved people while denying the freedom of speech to all women. She and Mott would, in the years to come, do something about it. Even as they left the final session of the convention, walking arm in arm into the London sunset, they “resolved to form a convention as soon as we returned home, and form a society to advocate the rights of women.”11

❦❦❦

Eight years would elapse before the convention that Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott had brainstormed became a reality. Once they returned to America—Stanton to Johnstown in upstate New York, Mott to Philadelphia—the two saw each other only occasionally. Once, in Boston the year after their London trip, Mott recalled their briefly discussing the idea of a “woman’s rights convention.”12 But other priorities intervened for both women.

Stanton immediately started a family, which grew to three young sons by the time of the convention. (She would eventually raise seven children.) She also took sole responsibility for this growing household, while her husband read for the bar and began practicing law.13 Mott, meanwhile, chose to expand her antislavery activism. She had co-founded the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society seven years earlier, when women were denied membership in the American Anti-Slavery Society.14 Now, as she saw her youngest child off to boarding school, she could devote even more time to the anti-slavery cause.15 Even so, her speeches, lobbying efforts, fundraising, and organizing now included advocacy for women’s rights and the relief of poor women.16

In 1842, eighteen months after her London introduction to Mott, Stanton attended an abolitionist meeting in Boston’s historic Faneuil Hall, where for the first time she heard the celebrated antislavery orator Frederick Douglass. Listening to this remarkable man speak before an enthusiastic audience of over four thousand, all of whom had braved the icy streets and the freezing January winds off the Boston waterfront just to be there on this Friday night, Stanton was awestruck. Douglass, she felt, eclipsed all the other speakers in the evening’s star-studded lineup. One of those speakers, Harvard Law School product Wendell Phillips, apparently agreed with her assessment. Stanton overheard him say, to the eminently literate poet, novelist, and journalist Lydia Maria Child, that while Douglass “has only just graduated from the ‘southern institution’”—a sarcastic euphemism for slavery—he “throws us all in the shade.”17

The impression Douglass made on Stanton would last a lifetime. On the occasion of his death more than forty years later, she would recall him as “the only man I ever knew who understood the degradation of disfranchisement for women.”18 Many other men, of course, joined the battle for women’s suffrage. But that is not what Stanton meant. Lydia Child had put it succinctly in her reply to her fellow abolitionist Phillips on that long-ago January night at Faneuil Hall. Because of his years in bondage, she said, Douglass “knows the wrongs of slavery subjectively,” whereas white men can “speak only from an objective point of view.”19 It was for the same reason that Douglass was determined to fight the battle for women’s right to vote. As a man born without legal rights of any kind, he understood.

In expressing why women and enslaved Black people would be the most genuine advocates for abolition and suffrage, Child’s insight also encapsulated the moral concordance between the antislavery movement and the emerging suffrage movement. In the years ahead, Frederick Douglass would champion both of these causes that would forever change the United States for the better.

The Faneuil Hall experience was a prelude to the Stantons making Boston their new home. Just over a year later, Henry joined a law firm in Boston, allowing the family to relocate to the “cradle of liberty” that inspired both of them. For Elizabeth in particular, Boston was exhilarating. This was the very hub of the nation’s abolitionist activity—the home of William Lloyd Garrison’s antislavery publication, The Liberator, and the intellectual crossroads of many of the nation’s leading writers, academics, and social reformers. She and Henry were immediately swept up in the current of the city’s regular abolitionist dinners and gatherings.

In the years ahead, most of the nation’s leading abolitionists would join Stanton in her battle for women’s suffrage.

In quick succession Elizabeth was introduced to an array of abolitionist celebrities that included Lydia Maria Child, Abby Kelley, John Greenleaf Whittier, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Paulina Wright, Louisa May Alcott, James Russell Lowell, Theodore Parker, Maria Chapman, Sydney Howard Gay, Parker Pillsbury, Stephen Foster, Wendell Phillips, and, crucially, Frederick Douglass.20 No longer would these people be distant, unapproachable demigods. Henceforth, they were Elizabeth Stanton’s flesh-and-blood compatriots, her mentors, and in many cases her friends. In the years ahead, most of them would join her in the battle for women’s suffrage.

The Stantons’ exciting and eventful life in Boston would last, however, for only two years. Henry’s delicate health could not withstand the Boston winters, and so the family prepared to abandon the splendid house that Elizabeth’s father had purchased for them on the Chelsea hills overlooking Boston Harbor. But before they did so, Elizabeth—who had recently given birth to her third son—hosted a small dinner party at their home for four leading lights of the antislavery movement, demonstrating that by this time she herself was well integrated into such elite company.20

Two of her invitees were Yale graduates: Joshua Leavitt, a lawyer and clergyman who edited the official newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society, The Emancipator, and John Pierpont, a nationally-known abolitionist poet and clergyman whose stirring verses were widely published and often publicly recited.

John Greenleaf Whittier, even more famous for his abolitionist poetry, was a third guest. Whittier had been arguing for women’s right to vote and women’s political equality for at least the last five years.21 He and Elizabeth first met at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840, and since then, the Stantons had been guests at his Massachusetts farm. In addition to his literary work, Whittier had been a state legislator, made an unsuccessful run for Congress, and published the influential Whig journal, the New England Weekly Review. Now, he was publisher of the abolitionist Pennsylvania Freeman.

Leavitt, Pierpont, and Whittier were all destined to join Elizabeth Stanton as advocates for women’s suffrage in the battles that lay ahead.

Rounding out this distinguished group of antislavery luminaries was another young Bostonian, the Harvard-trained lawyer Charles Sumner. His abolitionist sentiments and his affinity for poetry fused in his personal friendship with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whose collection of antislavery verse, Poems on Slavery, had been published three years previously at Sumner’s urging.22 The promising attorney had already begun to make a name for himself with his well-reasoned legal arguments in the antislavery cause.23

Seated on the upper-floor piazza of the Stantons’ residence, the group of like-minded friends could gaze out over the silhouettes of the many vessels lying at anchor in the harbor, and admire the outlines of the newly completed Bunker Hill monument. On this particular evening, Elizabeth Stanton and John Whittier could share memories of their indignation over the affronts to women at the London convention a half decade before, as she later recalled they did at least once at her home.24

John Pierpont likely followed his custom of reciting from his latest works. Charles Sumner, fluent in American history and recently elected to membership in the prestigious American Antiquarian Society, might have shared some insights into the Revolutionary War battle commemorated by the twilight-illuminated obelisk across the bay, or recalled some of Daniel Webster’s memorable words at the monument’s recent unveiling.25

These memories of their famous friends in Boston would accompany the Stantons to upstate New York, where for the next thirty-seven years they would live in the beautiful Finger Lakes region, a relatively milder microclimate better suited to Henry’s fragile health. The property they chose was located along a branch of the Erie Canal some thirty miles south of Lake Ontario, in a little town called Seneca Falls.26

Elizabeth’s father purchased this property for them, too, just as he had their residence in Boston. It consisted of some five acres, including a house that, in Elizabeth’s view at least, required extensive renovation before she and her family could move in. Throughout the summer of 1846, while spending her days minding the children and working with carpenters, painters, paperhangers, and gardeners, she devoted the evenings to her mother and her older sister, both of whom lived nearby. Yet still she found time to lobby the members of the state constitutional assembly which was then meeting in Albany for changes to the New York Constitution—to grant women the right to vote.

Even when she could not break free from her new homestead-in-progress in Seneca Falls, she managed to get some lobbying in. “Sitting on boxes in the midst of tools and shavings,” she and Ansel Bascom, the former mayor of Seneca Falls, would have “long talks” on “the status of women.” At the time, Bascom was a delegate to the New York constitutional convention. For Elizabeth, this made him a target of opportunity not to be missed. “I urged him to propose an amendment to Article II, Section 3, of the State Constitution,” she wrote in her autobiography. Her proposed change was “striking out the word ‘male,’ which limits suffrage to men.”27

Bascom fully agreed with her sentiments, but demurred on the point of actually offering an amendment. It would, he worried, make him “the laughing-stock of the convention.” Yet he would eventually overcome his fears on that score. He would later become one of the organizers of Stanton’s Woman’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, now barely two years in the future.

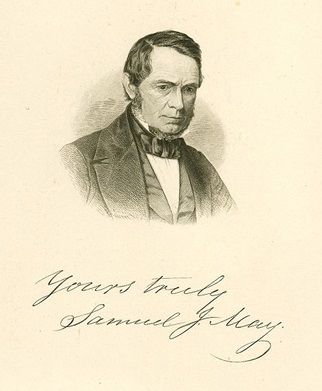

Meanwhile, Bascom and his fellow delegates in Albany found they could not avoid embarrassment by ducking the subject of women’s rights any more than by embracing it. Outside the state capitol, they drew criticism from one notable quarter precisely because their new constitution failed to address the subject. “During the past summer, a large Convention of delegates, elected by the people of this State, have been in session at the Capitol, framing a new Constitution,” the Reverend Samuel May announced to the congregants of the Unitarian Church of the Messiah in Syracuse. One would “hardly suspect,” he continued, “from the document they have spread before their fellow citizens, that there were any women in the body politic.”

In November 1846, the Reverend Samuel May set out all the arguments for women’s suffrage that would eventually be heard in state legislatures and the halls of Congress over the next three-quarters of a century.

Not only did the constitution fail to grant women the right to vote, May complained, but women were entirely excluded from the ratification process when the constitution was put before the people. “This entire disfranchisement of females is as unjust as the disfranchisement of the males would be,” he observed, “for there is nothing in their moral, mental or physical nature, that disqualifies them to understand correctly the true interests of the community.”

For nearly forty minutes, in a sermon that would soon be widely published, May set out all the principal arguments for and against women’s suffrage that would eventually be heard in state legislatures and the halls of Congress over the next three-quarters of a century. In logical fashion, he demolished every one of the common objections.

Women do not have the same logical faculties as men: And yet, May rejoined, for centuries women have been sovereigns as well as advisors to kings and emperors, and made their marks in literature, political economy, and the arts and sciences.

Women are physically weaker than men: Not necessarily, and in all events it is wisdom, not brute force, that is essential to casting one’s vote.

Women should not be exposed to the rigors of political engagement: To the contrary, if political meetings are unsuitable for women because they are filled with anger, ribaldry, and abuse, they are just as injurious to the moral health of men. It is no worse, said May, “for women to be thus defiled than for us men.”

As for the objection that women should not speak in public, May had a simple answer. “To me, it is as grateful to hear words of wisdom and eloquence from a woman as a man; and quite as uninstructive and wearisome to listen to a vapid, inane discourse from the one as from the other.”

He agreed that women should not neglect their homes, lest the family be destroyed, but protecting home and family was not women’s unique responsibility. The family, he said, “is the most important institution upon earth,” and therefore it must never be neglected “by the father any more than the mother.” Indeed, fathers feeling free to abandon their homes was by far the more serious problem.

As a man of the cloth, May dealt with the religious objection to woman’s equality very seriously. And while these remarks were initially addressed to his Syracuse congregation in November 1846, he had a broader audience in mind: following the sermon, he published thousands of copies and distributed them widely throughout America and Britain.28 Since the vast majority of active churchgoers in America and Britain in the mid-19th century were Christians, reconciling his argument with the Christian Bible was of special importance.29

“Christianity,” May said, requires that woman be treated not as “the slave of man … but as his nearest friend, his equal companion.” Turning to scripture, he pointed out how prominently women featured in the history of Jesus.

“They were not only his most ardent friends,” May said, but also “his most courageous followers”—and while the apostles shrank, the women “were last at his cross, and earliest at his grave.”30 Finally, he quoted the New Testament: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”31

May had come to his views on equality of the sexes in the previous decade, when he worked alongside Lydia Maria Child, Lucretia Mott, and the many other women who were active in the cause of abolition in New England. In 1837, after hearing favorable reports of speeches in New York and Boston by two prominent South Carolina abolitionists, Angelina and Sarah Grimké, he invited them to speak at his church. During a whirlwind week in October, the pair lectured not only to May’s congregation but at a half-dozen other venues, some with audiences exceeding 600 women and men. May was overwhelmed by the presentations from both women, based on their personal experiences as daughters of a slaveholding family. Never before had he “heard from any other lips, male or female, such eloquence.”

The idea that these women, simply because of their sex, should be prevented from participating in public affairs was to him “a miserable prejudice.” Ever since that time, May wrote in his autobiography, he held firmly to the view “that the daughters of men ought to be just as thoroughly and highly educated as the sons, that their physical, mental, and moral powers should be as fully developed, and that they should be allowed and encouraged to engage in any employment, enter into any profession, for which they have properly qualified themselves.” He added that “women ought to be paid the same compensation as men for services of any kinds equally well performed.” Above all, women should have the right “to take part in the public counsels … by their votes.”32

A decade later, these desiderata would become the creed of a national women’s rights movement that Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others would lead.

Samuel May delivered his Syracuse sermon at the very time that Stanton was remodeling her new home in nearby Seneca Falls. With renovations now sufficiently far along, the Stanton family—which by this time had grown to five—were able to move in a few months later, during the spring of 1847. Later that same year, Frederick Douglass, with whom Henry and Elizabeth were long since well acquainted, would begin moving his family to Rochester, just over fifty miles from the Stantons in the opposite direction.

Douglass had recently returned from an extended speaking tour in Great Britain and Ireland, so that now the Stantons would be able to see him frequently.

Coinciding with his move to New York, Douglass had just started a new publishing venture, a weekly antislavery newspaper which he christened The North Star. The first issue appeared on December 3, 1847. The following motto featured prominently beneath the masthead in this and every subsequent edition of the paper:

RIGHT IS OF NO SEX – TRUTH IS OF NO COLOR –

GOD IS THE FATHER OF US ALL, AND WE ARE BRETHREN

It is doubtful the Woman’s Rights Convention that would soon take place in Seneca Falls could have been as successful as it was, were it not for his assistance. In truth, the convention was a poorly planned event, conceived and executed all on the spur of the moment. When Elizabeth’s friend and mentor Lucretia Mott invited her to spend the day with a group of “thoughtful” Quaker women, neither of them had any idea that by sunset they would have decided to move forward with their long-ago daydream of a convention. Even more astonishing is that they proposed to pull it off, without any prior notice to anyone, a scant six days later.

The impromptu planning meeting that produced what Stanton would later call “the most momentous reform that had yet been launched on the world” took place at the home of Richard Hunt, a wealthy lawyer, abolitionist, and friend of Elizabeth’s father who lived in the neighboring village of Waterloo, just a short carriage ride away. Here, beyond the four Doric columns that guarded the entrance to the Hunts’ stately Federal-style red brick mansion, Elizabeth joined the guests she knew and those she did not in torrents of “vehemence and indignation” aimed at society’s wrongs towards women.

Among those impelled to immediate action by this lively discussion were Hunt’s sister-in-law, Mary Ann McClintock; his wife Jane Hunt; and Lucretia Mott’s sister, Martha Wright. All were morally opposed to slavery, and all took leading roles in organizing the forthcoming convention, which they decided should occupy two full days in the middle of the following week.

With such a short time fuse, raising a crowd was an immediate challenge. Overnight, the group placed an announcement in the next day’s Seneca County Courier. Only women were invited to the first day; “the public generally” would be welcome on day two. The announcement listed only one speaker by name: Lucretia Mott, who was to address the convention on day two. But it added that not only “other ladies” but also “gentlemen” would be making addresses.33

Douglass, immediately upon seeing this announcement in the Courier, reprinted it in The North Star, which by now reached almost all of the abolition supporters in the area.34 The natural affinity of women’s rights and antislavery made Douglass’s target audience ideal for the purpose. His advertisement, moreover, almost certainly added to the modest complement of men who would turn out to join the convention.

Douglass came to his deep sympathy for the cause of women’s rights by virtue of his own experience, not just as a formerly enslaved person who still lacked most rights of citizenship, but also as the beneficiary of women’s benevolence at key points in his life when he most needed it. During his boyhood in slavery it was a woman who, at considerable risk to herself, violated state law to teach him to read. When, at age twenty-one, he succeeded in escaping from bondage on his second attempt (after the first, he was apprehended and jailed), it was a brave woman, Anna Murray, who raised the money to finance his journey and hand-made the sailor’s disguise he wore. (Shortly afterward, he and Anna were married, a union that would last until her death forty-four years later.)

Relatively early in his career as an abolitionist public speaker in the North, Douglass frequently appeared alongside another woman, one of the most sensational orators of the antislavery movement: a former Massachusetts school teacher whom William Lloyd Garrison dubbed the “moral Joan of Arc of the world.” Through her well-reasoned arguments against slavery and for women’s equality, Abby Kelley served as a mentor to Douglass, convincing him that justice demanded the removal of all legal disabilities suffered not only by Black Americans but also women of all races.

The venue that Stanton and the other Seneca Falls convention planners chose was the logical one: the new Wesleyan Chapel on Fall Street, completed three years earlier with funds contributed by their host, Richard Hunt. Of late the chapel had been performing double duty as place of worship and town hall. With a footprint of about 2,800 square feet, roughly the size of a two-story, four-bedroom house, it could accommodate several hundred people. The building’s plain red-brick exterior, bereft of steeple or stained glass, made it more industrial-looking than ecclesiastical. And while less than imposing for such an historic occasion, its utilitarian aspect in subsequent decades would eventually yield to such prosaic uses as, variously, a grocery store, furniture store, plumbing company headquarters, opera house, office building, bowling alley, and laundromat.35

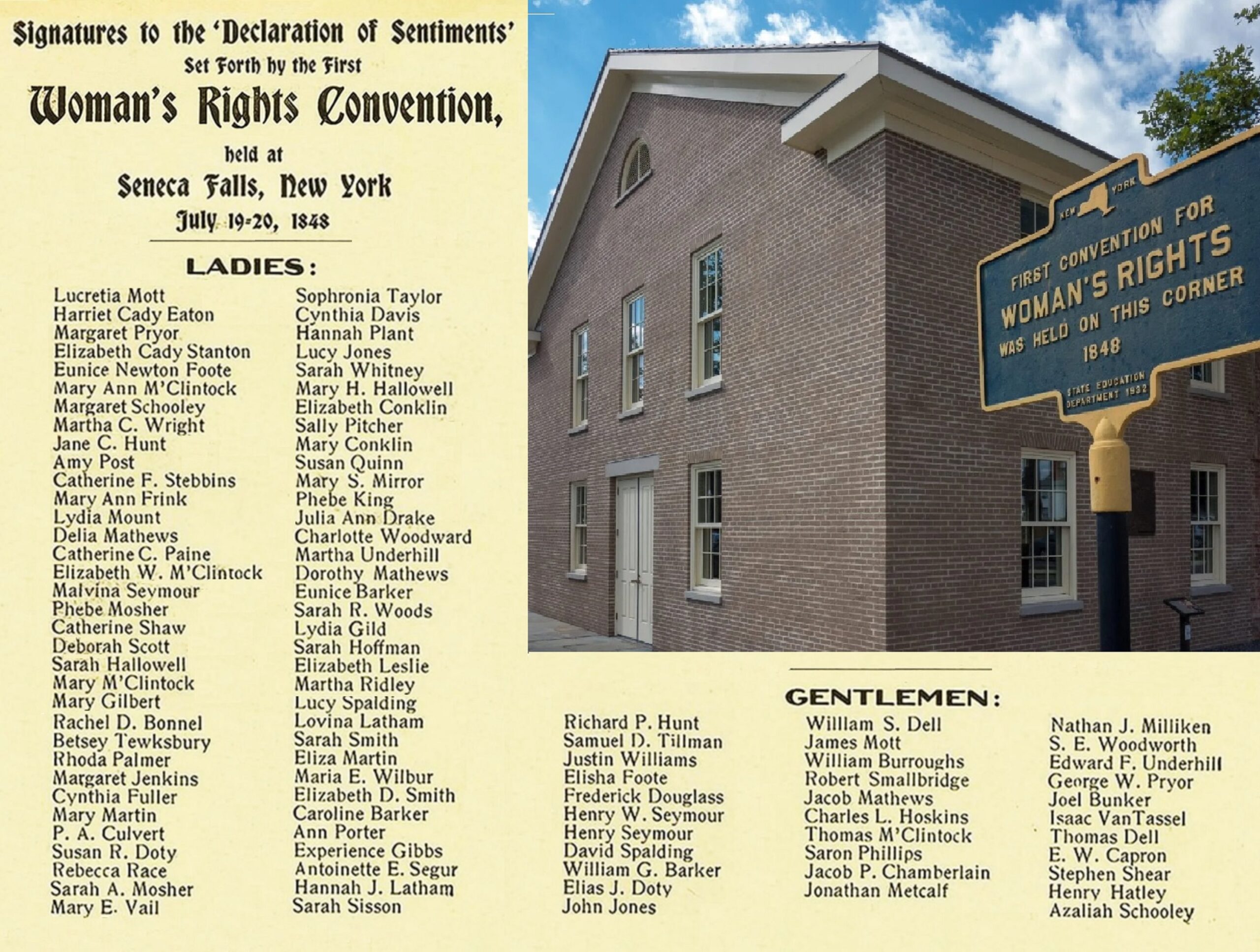

On July 19, 1848, at ten o’clock in the morning, nearly three hundred people crowded into this modest venue on a dirt road where antislavery activists routinely gathered. The crowd that filled the pews and packed the galleries on three sides on this particular Wednesday were there for a different reason: to “discuss the social, civil, and religious rights of women,” as the organizers had succinctly put it in their call to convention.

Just as James Madison and the Virginia delegation brought a ready-made prototype constitution in the form of the Virginia Plan to the 1776 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, allowing Madison to take the initiative in the proceedings, so too the Seneca Falls convention planners arrived with a model “Declaration of Rights and Sentiments” ready to be debated and approved. They had drafted it three days earlier in a reprise of their initial meeting at the Hunt mansion, with Stanton most often holding the pen. Both the name of the document and its style paid homage to the Declaration of Independence. It included a detailed list of specific grievances, notable among which was the denial to women of the “first right of a citizen, the elective franchise.”

The business of the convention began, surprisingly, with the seating of a man as chair of the proceedings. Although according to the published notice, men were not invited until the second day, several of them showed up anyway. The organizers not only relented but decided the men should “take the laboring oar through the Convention” and thus make themselves “useful.” In short order, Lucretia Mott’s husband James, a textile merchant and, though less famous than his wife, a leading abolitionist in his own right, was assigned the role of presiding officer.

The day was consumed with speeches—not only from women but also men, among them Elizabeth Stanton’s early recruit to the cause, Ansel Bascom. Only two weeks earlier in this same venue he had organized a meeting of the local Free Soil Party chapter, aimed at finding candidates for the Whig and Democratic Party tickets who would aggressively oppose slavery, which he called “the chiefest curse and foulest disgrace that attaches to our institutions.” Bascom himself was preparing to run for Congress, and in the years ahead would become intimately involved in the newly founded Republican Party.

On the first day of the convention, Stanton read the Declaration of Sentiments in full. With only minor amendments, it was approved unanimously—including the passage decrying the fact that women were denied the right to vote. The next day was devoted to the consideration of eleven implementing resolutions. These were debated thoroughly, and all but one were approved unanimously. The lone exception was resolution number nine, which declared that—

it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.

Despite the unanimous passage of a similar provision the day before, this particular resolution provoked spirited opposition. Unlike the previous day’s language, it not only complained of an injustice but stated very specifically what should be done to rectify it. This was an unequivocal demand to extending voting rights to women.

There were several strictly observant Quakers in the meeting. For them, the act of voting itself—whether by men or by women—posed a problem.36 Because of their strict pacifism, they refused to participate directly in government by holding office or voting.37 While petitioning government and seeking to influence it were allowed under Quaker orthodoxy, directly supporting a candidate, or voting for any office seeker, was not. This made it difficult to support a resolution calling the act of voting a “duty” and a “sacred right.”

Unlike Lucretia Mott, Stanton was not a Quaker, and she had drafted the resolution; but she was not alone in setting aside religious dicta in favor of what for her was a fundamental principle. Mott proved willing to do so, because she fully supported the simple justice of voting rights for women. So too did many of the other Quakers present that day. Yet even Mott worried about the political advisability of making it an immediate demand, and the risk that controversy over women’s suffrage would distract from the convention’s other discrete proposals such as reform of property, marriage, and divorce laws.38

There is no written record of how the more than two dozen men at the convention voted on the suffrage resolution, but only one of them spoke in support of it. This was Frederick Douglass, whose life story embodied the shared ideals of the abolitionist and suffrage movements. He joined Stanton in arguing that “the power to choose rulers and make laws [is] the right by which all others [are] secured.”39 An editorial he published the following week in The North Star, which very likely reprised the arguments he made at the convention, put the matter succinctly. “[I]n respect to political rights, we hold woman to be justly entitled to all we claim for man. We go farther, and express our conviction that all political rights which it is expedient for man to exercise, it is equally so for woman.” Douglass continued:

All that distinguishes man as an intelligent and accountable being, is equally true of woman; and if that government only is just which governs by the free consent of the governed, there can be no reason in the world for denying to woman the exercise of the elective franchise, or a hand in making and administering the laws of the land.40

Buoyed by Stanton’s insistence and Douglass’s eloquence, in the end the voting rights resolution was approved along with all the others.

As a final act before its adjournment, the Seneca Falls convention voted unanimously in favor of a measure offered by Lucretia Mott, which included this acknowledgment of the efforts by Douglass and the other men present that day:

RESOLVED, That the speedy success of our cause depends upon the zealous and untiring efforts of both men and women ….41

As a prediction, Mott’s parting words were only half correct. The process of securing women’s right to vote would be anything but speedy. But it would, to a certainty, require the efforts of not only women but men—sometimes violent men—in state and territorial capitals, the halls of Congress, and the White House.

— Christopher Cox

Footnotes

- Henry B. Stanton to Gerrit Smith, September 22, 1840, Gerrit Smith Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries; Norman K. Dann, Gerrit Smith: Practical Dreamer (Hamilton, NY: Log Cabin Books, 2009), 367; Octavius Brooks Frothingham, Gerrit Smith: A Biography (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1878), chaps. 4, 6; 212. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Eighty Years and More: Reminiscences, 1815-1897 (New York: European Publishing Company, 1898), 58-59; Henry B. Stanton, Random Recollections (New York: Macgowan & Slipper, 1886), 8; E. C. Stanton, Eighty Years and More, 58-59. ↩︎

- Resolution introduced by H. B. Stanton at the American Anti-Slavery Society Convention, October 1839, The Emancipator, November 14, 1839. ↩︎

- E. C. Stanton, Eighty Years and More, 59. ↩︎

- Ibid., 60-61. ↩︎

- Ibid., 72. ↩︎

- H. B. Stanton, Random Recollections, 74. ↩︎

- Sixth Annual Report of the Executive Committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society, with the Speeches Delivered at the Anniversary Meeting Held in the City of New York, on the 7th of May, 1839 (New York: William S. Dorr, 1839), passim. ↩︎

- Linda Christine Frank, “A Family Affair: The Marriage of Elizabeth Cady and Henry Brewster Stanton and the Development of Reform Politics” (PhD diss., University of California at Los Angeles, 2012), 14, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/22k374td. ↩︎

- Elisabeth Griffith, In Her Own Right: The Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 38-39; E.C. Stanton, Eighty Years and More, 81. ↩︎

- E. C. Stanton, Eighty Years and More, 82-83. ↩︎

- Lori D. Ginzberg, Elizabeth Cady Stanton: An American Life (New York: Hill and Wang, 2009), 42. ↩︎

- E. C. Stanton, Eighty Years and More, 136. ↩︎

- Carol Faulkner, Lucretia Mott’s Heresy: Abolition and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth Century America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 66. ↩︎

- Ibid., 118. ↩︎

- Ibid., 110, 117-18. ↩︎

- Leaflet, “Great meeting in Faneuil Hall for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia,” Boston, January 29, 1842, Library of Congress, Caleb Cushing Collection, Portfolio 57, Folder 28, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.05702800/; Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Eulogy for Frederick Douglass, as read by Susan B. Anthony, Metropolitan A.M.E. Church, Washington, D.C., February 25, 1895, in In Memoriam: Frederick Douglass, (Philadelphia: John C. Yorston & Co., 1897), 44. ↩︎

- E. C. Stanton, Eulogy for Frederick Douglass, 44. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid., 138. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds., History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 1, 1848-1861 (Rochester, NY: Charles Mann, 1881), 84. ↩︎

- Frederick J. Blue, “The Poet and the Reformer: Longfellow, Sumner, and the Bonds of Male Friendship, 1837-1874,” Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 15, no. 2 (Summer, 1995), 273-297; John Frederick Bell, “Poetry’s Place in the Crisis and Compromise of 1850,” Journal of the Civil War Era, vol. 5, no. 3 (September 2015), 399, 403. ↩︎

- See, for example, the excerpts from Sumner’s article in the January 10, 1843, Boston Advertiser reprinted in Edward L. Pierce, ed., Memoir and Letters of Charles Sumner: 1811-1874, vol. 2 (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1878), 238-39. ↩︎

- E. C. Stanton, Eighty Years and More, 139. ↩︎

- Sumner was elected to membership in the American Antiquarian Society in 1843, two years before this dinner at the Stantons. It was an especially prestigious recognition for a lawyer, in particular one so youthful. Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 1812-1849 (Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society), 448. ↩︎

- E. C. Stanton, Eighty Years and More, 138. ↩︎

- Ibid., 144-45. Bascom was the first president of Seneca Falls in 1831, as the mayor was then called. He was a delegate to the New York constitutional convention that opened on June 1, 1846, and adjourned on October 9 the same year. William G. Bishop and William H. Attree, Report of the Debates and Proceedings of the Convention for the Revision of the Constitution of the State of New York (Albany: Evening Atlas, 1846), 3. The constitution was approved by a statewide vote on November 3, 1846. Since Stanton’s autobiography states that she “moved” to Seneca Falls in the spring of 1847, the logical inference is that her conversations with Bascom concerning the “Convention, then in session in Albany” took place in the summer or fall of 1846, while renovations of what would be her new home were in progress and before the family moved in. The fact that the History of Woman Suffrage also mistakenly places the New York constitutional convention in 1847 is consistent with this interpretation. See E. C. Stanton et al., History of Woman Suffrage, 1:63. ↩︎

- Samuel J. May, Memoir of Samuel Joseph May (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1873), 190. ↩︎

- Roger Fink and Rodney Stark, The Churching of America, 1776-2005 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005), 56. Fink and Stark estimated that in 1850, 87.7% of all religious adherents in America belonged to one of six major Christian religions. England’s state religion was Christian. ↩︎

- Samuel J. May, “The Rights and Condition of Women,” sermon delivered November 8, 1846, in the Church of the Messiah, Syracuse, NY (Syracuse: Stoddard & Babcock, 1846). New York’s new constitution had been ratified by popular vote five days before this sermon, on November 3, 1846. Edna L. Jacobs, “New York’s Constitution a Hundred Years Ago,” New York History, vol. 28, no. 2 (April 1947), 191. ↩︎

- Galatians 3:28, Berean Study Bible version (modern vernacular). May quoted the King James version, the most widely used at the time. ↩︎

- Samuel J. May, Some Recollections of Our Antislavery Conflict (Boston: Fields, Osgood, and Co., 1869), 230-237. ↩︎

- E. C. Stanton et al., History of Woman Suffrage, 1:67. ↩︎

- David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 196. ↩︎

- Women’s Rights National Historical Park, Wesleyan Chapel Historic Structure Report: Historical Data Section (U.S. Department of the Interior, 1987), xiii–xv. ↩︎

- Paul Buckley, “Why Quakers Stopped Voting,” Friends Journal, October 1, 2016, https://www.friendsjournal.org/quakers-stopped-voting/. ↩︎

- Bradford Miller, Returning to Seneca Falls (Hudson, NY: Lindisfarne Press, 1995), 18. ↩︎

- Faulkner, Lucretia Mott’s Heresy, 140. ↩︎

- E. C. Stanton et al., History of Woman Suffrage, 1:73. ↩︎

- “The Rights of Women,” The North Star, July 28, 1848, 3. ↩︎

- E. C. Stanton et al., History of Woman Suffrage, 1:73. ↩︎