For two full days in the eighty-degree summer heat, behind closed doors in a stuffy, crowded hall, hundreds of women and men had focused single-mindedly on the subject of women’s rights. Now, as the double doors of the Methodist chapel were opened to the fresh air of a pleasant summer evening and its inhabitants spilled out into Fall Street, they stepped back into a world in which the battle over slavery remained the paramount concern.

Since most of those who attended the 1848 Woman’s Rights Convention were passionate abolitionists, this was their foremost concern, too. In fact it was the urgent priority of their daily lives. The presidential election was barely three months away. The incumbent in the White House, Democrat James Polk, was aggressively pursuing a policy of territorial expansion aimed at extending slavery across the North American continent. Polk himself was a slaveowner who, first as Speaker of the House and now as president, advocated policies that went far beyond the principles of states’ rights. In his zeal to protect slavery, Polk held that Congress must never use federal power to undermine slavery anywhere in the United States—even in states where slavery was outlawed.1

But Polk had promised to serve only one term, and was in ill health. Two months before the Seneca Falls convention, the Democratic National Convention had chosen as his successor the sitting president pro tem of the U.S. Senate, Lewis Cass of Michigan. To the opponents of slavery in Seneca Falls, Cass was no improvement. In the Senate, he had been a strong supporter of annexing Texas as a slave state and a reliable supporter of the slave interests. Now, in the runup to the election, a Democratic presidential campaign pamphlet quoting Cass’s views on “slavery in the southern States” proudly advertised his assertion that Congress had “neither the right nor the power to touch it.” Moreover, “even if we had both,” Cass assured the voting public, restricting slavery in any way “might lead to results which no wise man would willingly encounter.”2

The other major party nomination had just gone to Zachary Taylor, leader of the U.S. Army of Occupation in the Mexican War who had been courted by both the Democrats and the Whigs. Taylor had no prior political career and so, unlike Cass, no voting record. But as a southerner who owned plantations in Mississippi and Louisiana worked by slave labor, the newly-minted Whig could hardly be trusted to challenge slavery on moral grounds.

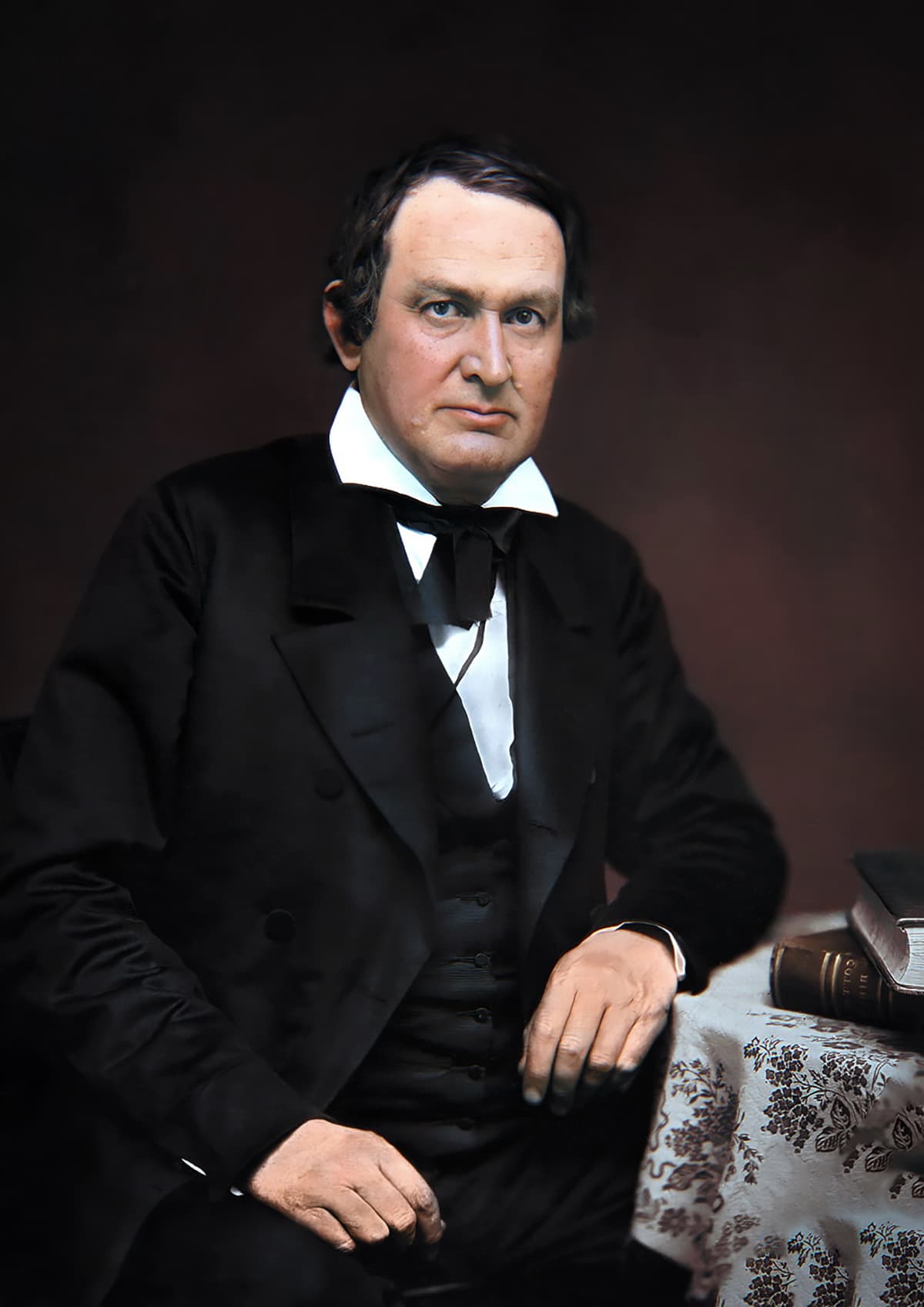

The intense concern with the presidential contest in and around Seneca Falls was not due solely to the fact that slavery was the overarching national issue of the day. There was a local angle as well: one of the candidates for president in the fall election was Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s cousin, Gerrit Smith. Six weeks before the 1848 Woman’s Rights Convention, Smith received the presidential nomination of the abolitionist Liberty League.3 As a minor party candidate, he had little hope of outpolling the Democratic and Whig nominees; but these were unusual times, when splinter parties could not only tip the balance in a close election but also influence the major party agendas. There was ample room for smaller parties to compete, given that the two-party system was of recent vintage in American politics. The modern Democratic Party was Andrew Jackson’s creation of just a generation ago, and the Whig Party had emerged in almost instant response to it, in the form of a broad anti-Jackson coalition. Both major parties were now only two decades old, and the shifting winds of politics were challenging them both, threatening their hold on the electorate.

Six weeks before the 1848 Woman’s Rights Convention, Smith received the presidential nomination of the abolitionist Liberty League. He had little hope of outpolling the Democratic and Whig nominees, but he could tip the balance in a close election.

Slavery, it seemed, was an issue too big for either party. Increasingly it divided the Democrats north and south, and it similarly cleaved the Whigs. Neither party had been organized around the slavery issue, and as a result both parties included pro- and antislavery factions. As Lincoln would famously say of the nation, a house divided cannot stand—and the biblical injunction was equally apt for the political parties of the day. In these fluid circumstances, as slavery increasingly became the dominant issue in contemporary politics, it was a commonplace that anything might happen.

In fact, something did happen: the Whig Party soon began to crumble, with Gerrit Smith’s Liberty League and its antecedent Liberty Party playing a significant, if evanescent, role in the Whigs’ demise. Nearly a decade before this summer of 1848, the Liberty Party had arisen out of a split within the antislavery movement itself. One faction, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s husband Henry and her cousin Gerrit, believed the best way to end slavery was through voting and participation in the political system. Followers of the influential William Lloyd Garrison, on the other hand, favored moral suasion, and abjured all participation in the corrupt political system of which slavery was an integral part. The Garrisonians refused to serve on juries, join the military, or vote. For opponents of slavery who supported practical political action, forming a political party was the logical next step. Thus was the Liberty Party born.

Early on, the newly created Liberty Party was successful in attracting a nucleus of antislavery Whigs, among them Lincoln’s future Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase.4 Within four years they had presented a national ticket for the 1844 presidential election. This incipient realignment in the nation’s politics, keyed to the issue of slavery, was a straw in the wind that portended the splintering and eventual end of one of the two major parties of the day.

The Liberty League platform of 1848 not only called for the abolition of slavery, but also demanded women’s right to vote—the surest sign yet that women’s suffrage was entering the national political conversation.

The emergence of the Liberty Party was significant not only for its emphasis on slavery, but also its attentiveness to the rights of women. Here, undeniably, was a new element in the nation’s politics. It was perhaps inevitable that this should be so, since by this time women were already prominent in the antislavery movement. After a number of the Liberty Party’s state organizations expressly granted their admission, women’s participation at the national level increased accordingly. At the party’s national nominating convention in Buffalo in 1843, Frederick Douglass’s friend and mentor Abby Kelley became the first woman to speak at a national political gathering. And hers was no token appearance: she boldly used the opportunity to challenge party strategy.5

Four years later, when the Liberty League emerged as an offshoot of the Liberty Party, women were not only convention speakers but full voting participants. At the party’s presidential nominating convention in June 1848, Lucretia Mott’s name was placed in nomination for Vice President of the United States. She finished fourth in the balloting, behind Frederick Douglass, who also spoke at the convention; George Bradburn, who had attended the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention and stood out for his speeches there against the exclusion of women;6 and eventual nominee Charles C. Foote.7 The Liberty League platform of 1848 not only called for the abolition of slavery, but also demanded women’s right to vote—the surest sign yet that women’s suffrage was entering the national political conversation.8

— Christopher Cox

Footnotes

- William Dusinberre, Slavemaster President: The Double Career of James Polk (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 173. ↩︎

- “General Cass on the Wilmot Proviso,” Democratic presidential campaign pamphlet, African American Pamphlet Collection, Library of Congress. ↩︎

- Thomas Hudson McKee, The National Conventions and Platforms of All Political Parties, 1789-1905, 6th ed. (Baltimore: The Friedenwald Co.), 70. ↩︎

- Reinhard H. Luthin, “Salmon P. Chase’s Political Career Before the Civil War,” Mississippi Historical Review, vol. 29, no. 4 (March 1943), 517; Walter Stahr, Stanton (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017), 49. ↩︎

- Reinhard O. Johnson, The Liberty Party, 1840-1848 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009), lxxv. ↩︎

- Frances H. Bradburn, A Memorial of George Bradburn (Boston: Cupples, Upham and Co., 1883), 76-82. ↩︎

- “The Liberty League Convention,” Michigan Liberty Press, June 30, 1848. ↩︎

- Walter Gable, Timeline of Events in Securing Woman Suffrage in New York State (Waterloo, NY: Office of the Seneca County Historian, 2017). ↩︎