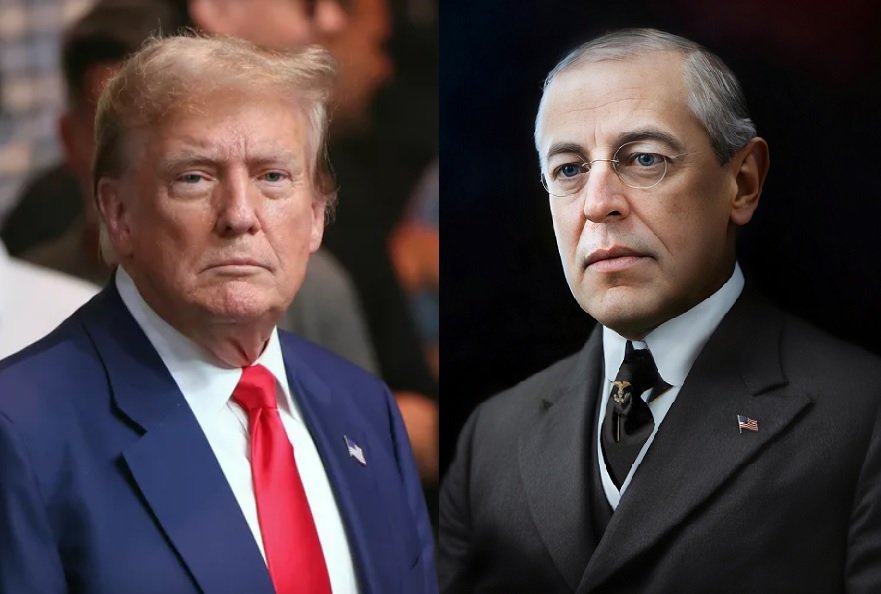

For all its made-for-meme moments, the 2024 presidential campaign may be remembered years from now for an unexpected reason: the resurrection of the tariff as a major campaign issue. Donald Trump’s proposals, and Kamala Harris’s response to them, brought tariff policy to a prominence in the national political debate that America hadn’t seen in nearly a century.

It is certainly a topic worthy of debate. Tariff policy has been at the center of long-running disagreements over the causes and contributors to some of the most pivotal events in American history, including the Civil War and the Great Depression.

In the nineteenth century arguments over the tariff featured prominently in presidential elections. Andrew Jackson won the White House in 1828 by opposing the record-high tariff rates Congress imposed that year—what southern critics derided as the “Tariff of Abominations.”1 Throughout the 1840s, protectionism defined the northern Whigs, including Abraham Lincoln. And in the pre–Civil War period, when the politics of slavery dominated all else, tariff policy—though less explosive—was nearly as efficient in dividing North and South.2

Tariff reform was the number-one issue in Grover Cleveland’s face-off against Benjamin Harrison in 1888. Harrison’s victory in that contest quickly led to the Tariff Act of 1890, which introduced steep tariff rates that further stoked the argument.3 Tariff policy gained top billing again in the 1892 Harrison-Cleveland rematch.

Four years after that, when William Jennings Bryan’s famed “Cross of Gold” speech earned him the Democratic presidential nomination, the tariff was second only to the gold standard as an issue in the campaign. The tariff, Bryan shouted from the podium at the Chicago convention, had “slain its thousands”—and “the gold standard has slain its tens of thousands!”4

Bryan thrice became the Democrats’ presidential nominee—and thrice failed to win the White House. Fellow Democrat Woodrow Wilson eschewed the Nebraskan’s attacks on the gold standard but assaulted the Republicans’ high-tariff policy with relish. Wilson began his political career by running for New Jersey governor in 1910. That race came only two years after Bryan’s last White House bid, and only a year after Congress passed the Payne-Aldrich Tariff. The widely unpopular measure gave Wilson a golden opportunity to talk about a major national issue during his statewide race.5

Wilson the southerner was steeped in anti-tariff tradition. The South’s cotton economy, heavily dependent on exports, got no benefit from protectionist trade barriers. The future president’s first overt political act, as a young man of twenty-five, was testifying against agricultural tariffs at a field hearing of the U.S. Tariff Commission.6 During his years on the faculty and as president of Princeton University, he repeatedly criticized protective tariffs in his writings and speeches.7

Timing is everything in politics, as Wilson discovered in 1910: it became the Democrats’ year across the nation, thanks in large measure to the Payne-Aldrich Tariff. The law’s far-reaching effects hit consumers, businesses, and farmers alike. President William Howard Taft had promised to lower rates, but after a bazaar for special interests in Congress, the law he signed included hefty tax increases on hundreds of items. It was an intensely partisan issue, too: the final vote in the House fell almost strictly along party lines. In the Senate, not a single Democrat voted for the legislation.8

The future president’s first overt political act, as a young man of twenty-five, was testifying against agricultural tariffs at a field hearing of the U.S. Tariff Commission.

Two years after being elected governor, Wilson became the Democrats’ presidential nominee in a three-way race against Taft and Theodore Roosevelt. The tariff did not emerge as the leading issue in that campaign, but once in office, Wilson made “tariff and currency reform” his top priority. The Revenue Act of 1913 gave the nation its first income tax under the new Sixteenth Amendment, and it slashed tariff rates to their lowest levels since 1857.9

Even the availability of the income tax as a new, alternative source of revenue did not tamp down the appetite for tariffs. Throughout Wilson’s two terms in the White House, northern manufacturers urged a return to the old policy. Their cause benefited from the unprecedented government demands for new revenues that came with America’s entry into the World War in 1917.

Even so, Wilson never shook his anti-tariff convictions. Instead he raised individual income tax rates to more than 70 percent and relied on billions in debt—the famous Liberty Bonds. But after the war, with America mired in recession throughout the election year of 1920, the Republican platform pointed the finger at the “staggering” income tax burden.10 Senator Warren Harding promised a “return to normalcy,” broadly understood to include lowering income tax rates and returning tariff rates to pre-Wilson levels.

Soon after Harding’s inauguration, Congress passed the Emergency Tariff Act in 1921, followed by the Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act in 1922.11 The legislation raised tariff rates, though not as high as the Payne-Aldrich rates of the Taft years. Harding died of a heart attack in August 1923, and his successor, Calvin Coolidge, did not ask Congress for any change in tariff law throughout his presidency.

Instead, Coolidge focused on reducing income tax rates from their wartime levels, bringing the top rate down to 25%. American exports increased every year from 1922 through 1929, rising 42%. Imports increased over the same period by 40%, even though the war-torn, deeply indebted economies of postwar Europe struggled to produce goods for shipment to the United States.12

Meanwhile, the U.S. economy grew at a robust rate of more than 4% per year.13 Wages and consumer purchasing power rose in tandem, thanks in part to the many advances in technology that increased worker productivity.14 The tariff might therefore have faded as an issue were it not for the recession that began during Herbert Hoover’s first year in office, and the government’s response to it.

Although the stock market was up 9% for the year when a precipitous selloff began in late October 1929, the economy was already in a mild recession that had begun in July.15 Stocks steadily recovered ground over the next six months,16 but fear of a prolonged recession prompted Hoover and many in Congress to propose what they considered stimulative economic measures, including a stiffening of protective tariffs. Within the space of five days in June 1930, the House and Senate passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act and Hoover signed it into law.17

The act’s chief sponsor, Republican Reed Smoot of Utah, touted the more than 20% increase in average tariff rates—with some duties increasing by as much as 50%—as a boon to the nation’s farmers. More than a thousand economists disagreed, sending Hoover an open letter urging him not to sign the bill.18 The warnings proved warranted when America’s trading partners responded by jacking up their own tariffs, igniting a worldwide trade war that cut the real value of international trade by more than 50% between 1929 and 1933.19

That is why, in 1934, Congress established a new trade framework, the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act. From that point until today, tariff policy receded from prominence.

Fear of a prolonged recession prompted Hoover and many in Congress to propose what they considered stimulative economic measures, including a stiffening of protective tariffs. In June 1930, Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act into law.

Still, the debate over the consequences of Smoot-Hawley has raged on. Was the tariff a fundamental cause of the Depression?20 Was it instead a contributor to the length and severity of the Depression? Or even to the monetary deflation of the Depression years?21 Alternatively, might Smoot-Hawley actually have helped stave off the Depression—by increasing the U.S. export surplus—as the conventional Keynesian argument would have it?22 And if so, where should the finger of blame point?

Back in 2002, then–Federal Reserve board member and future chair Ben Bernanke famously accepted blame for the Great Depression on behalf of the Fed. “Regarding the Great Depression,” Bernanke announced, “we did it. We’re very sorry. . . . We won’t do it again.” He was referring to the Fed’s increases in interest rates in 1928 and 1929. Intended to limit speculation in securities markets, the increases slowed economic activity in the United States and triggered recessions around the globe.23

But even blaming the Federal Reserve can’t get tariffs off the hook. In an influential paper for the Journal of Monetary Economics, the late economist Allan H. Meltzer—author of the multivolume History of the Federal Reserve—pointed to Fed mistakes but also highlighted the importance of tariff policy. Meltzer assigned “a large role to the Hawley-Smoot tariff and subsequent tariff retaliation in explaining why the 1929 recession did not follow the path of previous monetary contractions but became the Great Depression.”24

Tariffs have now reemerged as a leading issue. Supporters promote high tariffs as a key to national prosperity, while opponents point to the ultimate economic disaster—the Great Depression—as a stark warning of what could happen if tariff policy goes wrong. But all sides would agree on this: With stakes this high, the “new” political pastime of debating tariff policy will be time well spent.

—Christopher Cox

A version of this post previously appeared as an article in the Coolidge Review.

Footnotes

- An Act in alteration of the several acts imposing duties on imports, 20th Cong., 1st Sess., ch. 55, 4 Stat. 270-75 (1828). ↩︎

- Douglas A. Irwin, “Antebellum Tariff Politics: Regional Coalitions and Shifting Economic Interests,” Journal of Law & Economics, vol. 51, no. 4 (November 2008), 715-741. ↩︎

- Tariff Act of 1890, 51st Cong., 1st Sess., ch. 1244, 26 Stat. 567, 567-625. The legislation was controlled in the House by William McKinley of Ohio, chair of the Committee on Ways and Means, and became known colloquially as the “McKinley Tariff.” ↩︎

- William Jennings Bryan, “Cross of Gold” speech, July 8, 1896, in Speeches of William Jennings Bryan, 2 vols. (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1912), 1:238-249; Bryan, “The Tariff,” speech in U.S. House of Representatives, March 16, 1892, ibid., 1:3-77. ↩︎

- Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act, 61st Cong., 1st Sess., Pub. L. 61-5, ch. 6, [section] 1, 36 Stat. 11, 112-17 (1909). ↩︎

- Minutes of the American Whig Society, May 24, November 12, 1878, in Arthur S. Link, ed., The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, 69 vols (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966–94), 1:377, 434. ↩︎

- For example, Woodrow Wilson, “The Tariff Make-Believe,” North American Review, vol. 190, no. 647 (October 1909), 535–56, at 547. ↩︎

- 44 Cong. Rec. pt. 5, 61st Cong., 1st Sess. (July 31, 1910), 4755 (House roll call on conference report for H.R. 1438); ibid. (August 5, 1910), 4949 (Senate roll call on conference report for H.R. 1438); “Payne-Aldrich Tariff Bill Signed by the President,” Wall Street Journal, August 6, 1909, 1. ↩︎

- Revenue Act of 1913, 63rd Cong., 1st Sess., Pub. L. 63-16, 38 Stat. 114. ↩︎

- 1920 Republican Platform, in George D. Ellis, ed., Platforms of the Two Great Political Parties, 1856-1920, Inclusive (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1920), 235-256, at 245. ↩︎

- Emergency Tariff of 1921, 67th Cong., 1st Sess., Pub. L. 67-10, 42 Stat. 9-19; Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act, 67th Cong., 2nd Sess., Pub. Law 67-318, 42 Stat. 858 (1922). ↩︎

- U.S. Census Bureau, Series U 1-25, Balance of International Payments: 1790 to 1970, in Historical Statistics of the United States, Bicentennial Edition (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975), 864. ↩︎

- Series F 1-5, Gross National Product, Total and Per Capita, in Current and 1958 Prices: 1869 to 1970, ibid., 224. ↩︎

- Leo Wolman, “American Labor Since 1920,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, vol. 25, no. 169, supp. (March 1930), 158-163; Stephen B. Reed, “One Hundred Years of Price Change: The Consumer Price Index and the American Inflation Experience,” Monthly Labor Review (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 2014). ↩︎

- Table 3: Business Cycle Chronologies and Durations to 1938, in David Glasner, ed., Business Cycles and Depressions: An Encyclopedia (New York: Garland Publishing, 1997), 734. ↩︎

- Table 2, United States Index of Security Prices, Nov. 1929-Apr. 1930, in Lionel Robbins, The Great Depression (New York: MacMillan Co., 1934), 204. ↩︎

- Tariff Act of 1930, 71st Cong., 2nd Session, Pub. L. 71–361, 46 Stat. 590 ch. 497 (1930). ↩︎

- Open letter signed by 1,028 economists regarding proposed upward revision of tariff rates, 72 Cong. Rec. pt. 8, 71st Cong., 2nd Sess. (May 5, 1930), 8327-8330. ↩︎

- David Glassner, “Smoot-Hawley Tariff,” in Business Cycles and Depressions, 630. ↩︎

- Jude Wanniski, The Way the World Works (New York: Basic Books, 1978). ↩︎

- David Glasner, Free Banking and Monetary Reform (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 123-24. ↩︎

- Barry Eichengreen, “The Political Economy of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff,” NBER Working Paper 2001 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 1986). ↩︎

- Gary Richardson, “The Great Depression,” Federal Reserve History (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2013), FederalReserveHistory.org. ↩︎

- Allan Meltzer, “Monetary and Other Explanations of the Start of the Great Depression,” Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 2, no. 4 (November 1976), 455-471, at 460. ↩︎