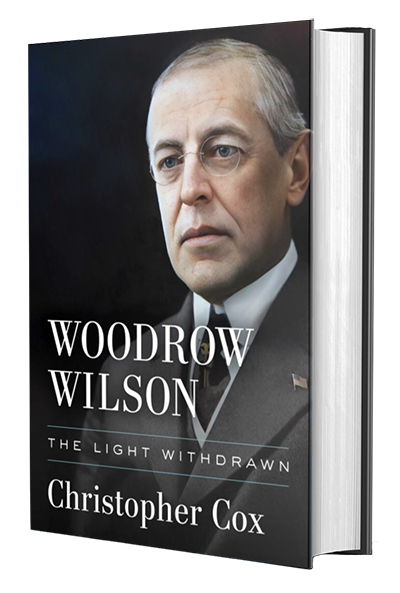

A timely reassessment of Woodrow Wilson and his role in the long national struggle for racial equality and women’s voting rights.

More than a century after he dominated American politics, Woodrow Wilson still fascinates. With panoramic sweep, Woodrow Wilson: The Light Withdrawn reassesses his life and his role in the movements for racial equality and women’s suffrage. The Wilson that emerges is a man superbly unsuited to the moment when he ascended to the presidency in 1912, as the struggle for women’s voting rights in America reached the tipping point.

The first southern Democrat to occupy the White House since the Civil War era brought with him to Washington like-minded men who quickly set to work segregating the federal government. Wilson’s own sympathy for Jim Crow and states’ rights animated his years-long hostility to the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, which promised universal suffrage backed by federal enforcement. Women demonstrating for voting rights found themselves demonized in government propaganda, beaten and starved while illegally imprisoned, and even confined to the insane asylum.

When, in the twilight of his second term, two-thirds of Congress stood on the threshold of passing the Anthony Amendment, Wilson abruptly switched his position. But in sympathy with like-minded southern Democrats, he acquiesced in a “race rider” that would protect Jim Crow. The heroes responsible for the eventual success of the unadulterated Anthony Amendment are brought to life by Christopher Cox, an author steeped in the ways of Washington and political power. This is a brilliant, carefully researched work that puts you at the center of one of the greatest advances in the history of American democracy.

Special Features

Gallery of Leading Characters

Come face-to-face with figures from the past, restored and brought to life in color with great care for historical accuracy.

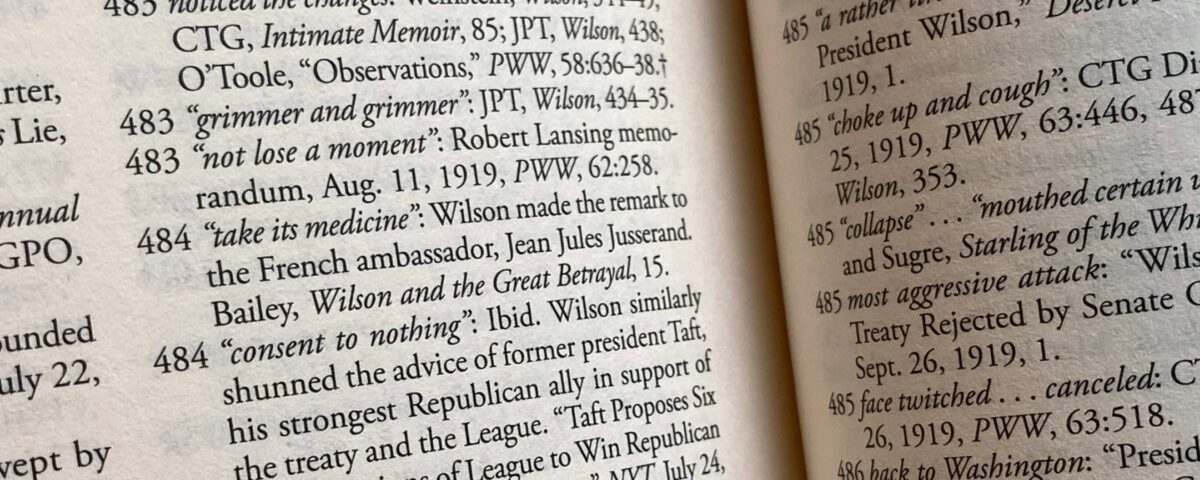

Extended Notes

View and search online or download printer-friendly pdfs of additional content and source material not included in the printed book.

Read an Excerpt

During their two-year engagement that began on September 16, 1883, Woodrow Wilson and Ellen Axson exchanged more than seven hundred letters. Woodrow in Baltimore was the more frequent correspondent, often devoting several pages to himself—his challenges, his political thinking, his health, his insecurities, and his ambitions. Ellen, first from Georgia and then New York City, where she studied at the Art Students League, willingly shared in his self-analysis. To his reflections she added her own appraisals, in turn leading him to further introspection. But even the sensitive and accommodating bride-to-be occasionally warned him against too much solipsism. “‘Know thyself’ may be a very good motto,” she gently chided five months into their engagement, “but there are others still better, for instance, ‘forget thyself.’”

Shortly before the wedding ceremony, the prospective groom wrote Ellen from Johns Hopkins to complain about the then-emerging popular wisdom of “a woman’s right to lead her own life,” independent from an existence as auxiliary to husband and children. This, he assured her, was a “pernicious falsehood.”

Coming Events

No events scheduled at this time.

Media